My interest in languages has led to some interesting places, working on languages from different families in various contexts. Most recently I’ve been curious about the ways that languages develop over time, such as in relation to word order. This was part of the reason I started to work on syntactic reconstruction - describing the grammar of a language like Pnar with the relatively rare verb-initial word order made me wonder about the reasons behind such patterns.

Other researchers have worked on word order for a long time, as reflected by the various typological databases that store information on word order for multiple languages (i.e. WALS, Grambank, AUTOTYP), but there are various concerns with this kind of information, which I discovered when I attempted to access/update it.

One issue with many typological databases is that the sample is fixed - you can’t add information for languages that you know. This means that you are stuck with the size of the dataset as-is. It can’t be expanded, and in many cases can’t be updated. There are various reasons for this (not all of them bad), but it is a bit of a drawback in my mind.

Another issue is that the categorizations for word order depend on expert determinations. Again, this is not necessarily a bad thing, but it means that if there are multiple (sets of) criteria determining what “word order” is for a given language, someone has to make a choice regarding which (set of) criteria to follow, which risks inconsistency.

As I mentioned in a previous post, the taggedPBC was developed to address some of these issues, and as part of the process I submitted a paper to discuss some of the concerns. The paper has now been published with Springer Nature in the journal Language Resources and Evaluation, and you can view/read it for free here. This post serves as an introduction/summary of the main points in relation to word order.

Why another database?

It’s worth noting that there are quite a few language databases available for crosslinguistic/comparative research. Some provide information about languages, while others provide language data. The former are typified by typological databases, with sparse but broad coverage, and the latter are typified by individual language corpora with narrow but detailed coverage. There are very few databases that contain a large quantity of actual data for a large number of languages. Even rarer are datasets that allow for extraction of features directly from corpora. For those datasets that do allow for extraction of features, the data is generally not parallel, which means that the contexts of language use are very different and thus more difficult to compare. Of course parallel text can have its own issues, but I might make that the subject of another post.

This set of problems were what I wanted to develop the taggedPBC to address: a large dataset of language corpora with baseline annotations that allow researchers to extract features directly from the underlying data. Additionally (ideally) this would be a database that could be expanded and improved, and it should have a high degree of comparability.

Developing the taggedPBC

The taggedPBC builds on previous work by Mayer & Cysouw 2014. In the Parallel Bible Corpus (PBC) they gathered Bible translations from a large number of languages for crosslinguistic research. The taggedPBC extends this dataset in two ways:

- Sourcing additional translations to increase the number of represented languages from 1,597 languages to 1,942.

- Tagging each language corpus for part-of-speech via crosslingual tag transfer.

The first extension is relatively straightforward, as all we need to do is search for digital Bible translations of languages that are not represented in the original PBC. The second extension is a bit more tricky. For one thing, how do you tag parts of speech for a low-resource language given all you have is a parallel text? For another, how do you assess the quality of the tagging? And finally, is the resulting tagged corpus even useful?

Tagging low-resource languages

By parts of speech (POS) NLP practitioners typically mean what other linguists might refer to as “word classes”. These are distinctions like “nouns” and “verbs” (which occur in pretty much all languages) or “adjectives”, “adverbs”, and “numeral classifiers” (which occur in a more limited set of languages). Whether something fits into a particular class depends on a word’s function (meaning), distribution (location in a stream/string/sentence), and associated grammatical categories (relation to other words). The observation here is that particular criteria for a word class may differ slightly from language to language. There is some pretty good evidence that these classes of words are meaningful with regard to how humans process language, which means it is worth trying to tag them in a given language.

However, the fact that criteria for POS may be different depending on the language makes it a bit difficult to map tags between languages. One way of doing this tagging for an individual language involves manually tagging some language data, then training a statistical computational model to “recognize” the context for a given tag. This is a classification problem and is often used to introduce machine learning concepts in NLP. Unfortunately this approach isn’t particularly viable when you don’t have much manually annotated data.

Some research2,3 has shown success with transferring tags from high-resource languages to low-resource languages via word alignment, given parallel texts. Since parallel texts are what make up the PBC, this is the approach I followed, after reducing the overall set of verses to increase the odds of alignment (see details in the paper).

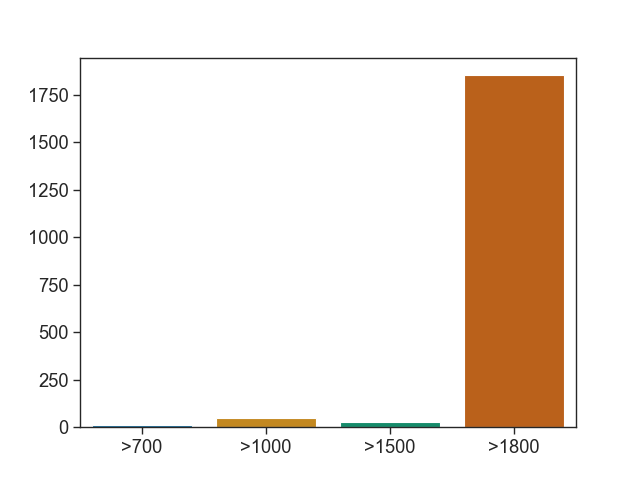

This results in 1,885 tagged verses for the majority of languages in the PBC, giving the following counts of verses/languages in the corpus:

| Number of verses | Number of languages |

|---|---|

| 1800+ | 1853 |

| 1500-1800 | 27 |

| 1000-1500 | 50 |

| 700-1000 | 12 |

| Total | 1942 |

Assessing tag quality

Now that we have a dataset of tagged corpora, we can start to conduct research, right? Well, not exactly. How do we know that the tagging methodology gives “good enough” results that such tags can be used for research? If the results are basically garbage, any research based on them isn’t really worth much. We need to conduct some validation procedures to assess the quality of the method.

For this, I decided to compare the word-alignment + tag transfer method with individual automatic pos-taggers developed for high-resource languages. It just so happens that the SpaCy and Trankit libraries have semi-supervised pretrained pos-taggers for multiple languages that are also represented in the taggedPBC. When we compare with the crosslingual tag transfer method I used, the correspondence is over 75% between the methods for both nouns and verbs, across both libraries.

This indicates that the tag quality of the word-alignment method gives decent results, even for low-resource languages, and that it can at least identify nouns and verbs relatively well.

Extracting features

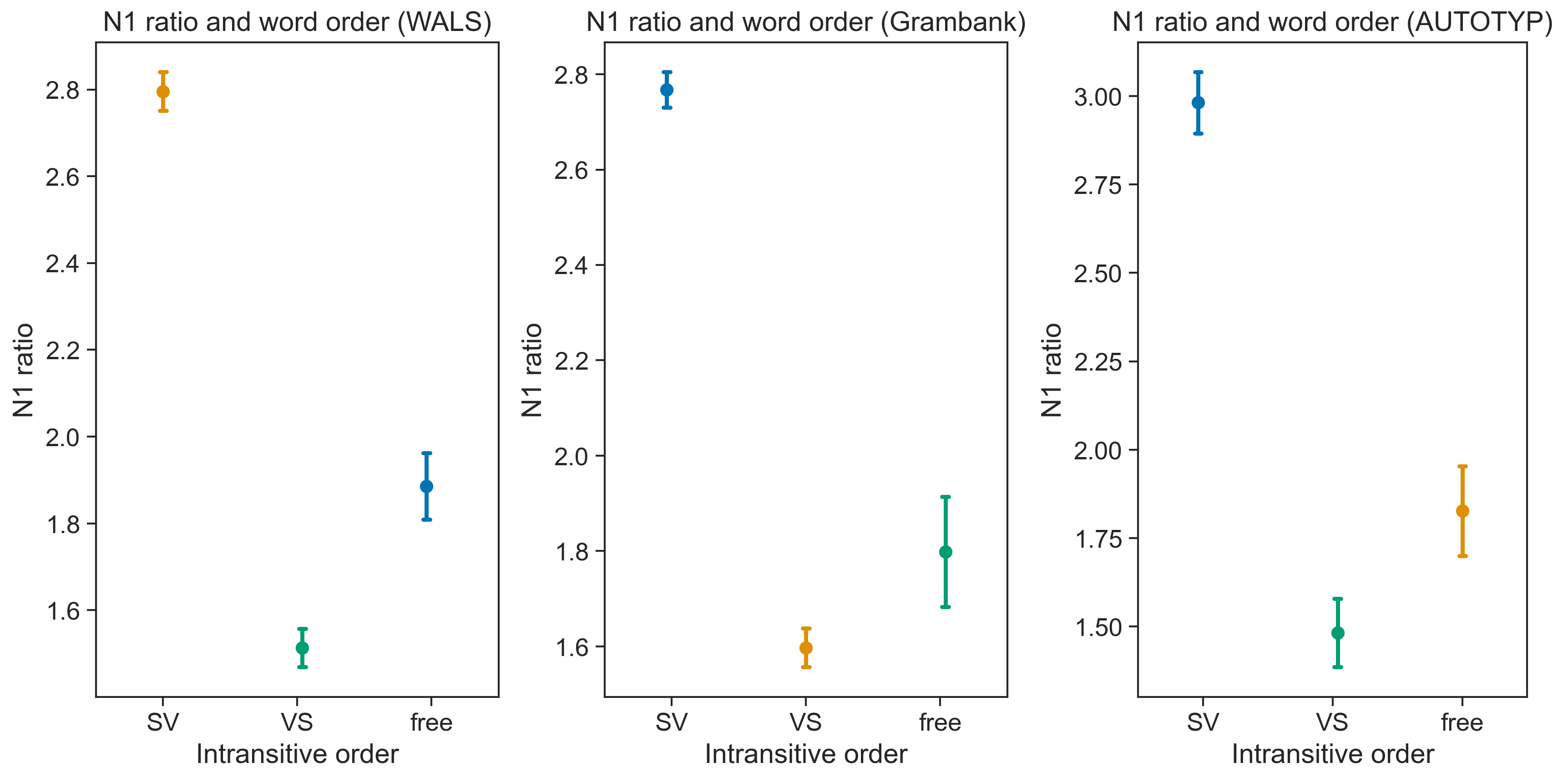

Another test we can do is to assess how well features derived from the tagged data correspond to well-known linguistic distinctions, as measured in typological databases. For this I decided to investigate word order. In particular, I focused on intransitive word order, namely the order of the “argument” and “predicate” in clauses that require a single agent/patient in relation to the action/state (more details on these distinctions in the paper).

To identify a measure for word order from each corpus, I essentially counted orders of arguments and predicates in verses containing both, then divided the “argument-first” verses by the number of “predicate-first” verses to derive the “N1 ratio”. I then observed the correlation between this (continuous) variable and intransitive word order classifications in three typological databases.

The findings were quite striking. In all cases, the N1 ratio significantly differentiated between SV and VS word order classifications, and in most cases also differentiated between those orders and “free” word order. I conclude from this that the N1 ratio (a corpus based measure) is a good proxy for word order. And given a decently tagged corpus, it is relatively easy to derive.

Future work

So what does this mean? Basically it means that the taggedPBC is a good baseline for crosslinguistic research. The fact that there is even a small amount of tagging for parts of speech for all languages represented means that there are a lot of opportunities to investigate those word classes. Some of the possibilities include:

- Extracting additional features (phonological, lexical, morphological, syntactic) that correlate with typological observations.

- Observing correlations with theoretical constructs and historical patterns.

The benefit of the approach I’ve taken here is that data can be added, features can be expanded, and different criteria can be used to determine features of interest. Additionally, the collaborative aspect of this work is supported by the infrastructure and workflows provided by Github.

There’s still a lot to be done. For any given corpus in the taggedPBC, there are a lot of unknown tags. Because of this, one of my primary goals is to expand the annotations, hopefully through collaboration with native speakers and with other linguists. I’ve started making some progress toward that goal, but there is still a ton of work to do.

References

[1] Mayer, Thomas & Michael Cysouw. 2014. Creating a massively parallel Bible corpus. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14), pages 3158–3163, Reykjavik, Iceland. European Language Resources Association (ELRA). https://aclanthology.org/L14-1215/

[2] Agić, Željko, Dirk Hovy, & Anders Søgaard. 2015. If all you have is a bit of the Bible: Learning POS taggers for truly low-resource languages. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers), pages 268–272, Beijing, China. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/P15-2044/

[3] Imani, Ayyoob, et al. 2022. Graph-Based Multilingual Label Propagation for Low-Resource Part-of-Speech Tagging. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 1577–1589, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/2022.emnlp-main.102/